Home > River to Rail > Boom & Bust

River To Rail: Boom & Bust

Without River & Rail Traffic

Madison would not be what it is today without it. River traffic fueled explosive growth that made Madison the larget city in the young State of Indiana. Rail traffic made Madison the keystone of the growth of Indiana's interior. However, it was the same growth that sapped the life from Madison.

Living High on the Hog

Pork packing and its related businesses were an important part of Madison’s economy from its earliest days. In the mid 1830s Madison processed about 15,000 hogs but only 10 years later that number increased to more than 63,000 and it was still a growing business.

In the early days, and before the railroad, hogs were allowed to run wild foraging in the woods. They existed on what was called “mast,” a combination of nuts and acorns and anything else they could found on the forest floor. It took considerable time to fatten a hog on mast, but as one farmer remarked, “What’s time to a hog?” In the fall, when the weather turned cold, a farmer would gather as many suitable hogs as he could find and head them towards the packing houses in Madison. Some traveled from many miles away and as they traveled they often combined with others to form herds of hundreds of protesting hogs. Dogs were usually employed to help keep the porkers in line and by the time they reached Madison, the results was a gathering of cranky pigs, snapping and snarling hounds and exhausted farmers. They proceeded right through town where the hapless hogs were put in holding pens to await their fate. When the railroad lines came into being the process was simplified. Farmers only had to meet the lines and load their charges into waiting cars.

Madison’s Pork Houses

Between 1847 and 1857 something like fourteen slaughtering and pork packing houses were located in Madison:

Thomas and Elijah Paine were on Main Street (now Jefferson Street) near the head of Crooked Creek. The spot was once called the “Old Mire” before the creek was straightened.

Near Fifth Street between Broadway and Elm, A. McNaughten ran a pork house. It later became White, McNaughten and Company and it was quite successful. By 1854, however, it was run by O’Neill, Bayley and Irwin.

The Mammoth Cave was built by David White and it was known as White and Cunningham Company. It was located on the far east side of town near the river at Fulton and Ferry Streets.

Godman and Sons along with Samuel Sering had an extensive plant in North Madison. It was located on the railroad tracks near the railroad complex and was built of stone (above). The windows were mere slits, perhaps to retain heat as the butchering was done during the coldest months. Godman also built a slaughter house on Crooked Creek in 1855.

Perhaps the most famous business was the Jenny Lind Pork House, so named because, much to her consternation she was required to sing there or forfeit the ticket money. It was located on High Street (now Second Street) and Mulberry.

William Clough who was later affiliated with the building of railroad cars, operated a pork concern on Central Avenue.

Jonathan Fitch for years packed pork from the building on the northwest corner of Main Cross and Walnut Street.

A. W. Flint ran a pork house at the foot of Vine Street which later became the depot for the P.C.C. & St. L. rail line. (The highlighted section of the photo was the original pork house)

There were other pork houses owned by Washer and Wharton; Powell and Hubbard; D. Blackmore; C. Friedersdorff; and Shrewsbury and Price, this one located on the river front on the curve of the railroad tracks near to the Palmetto Mills.

152,000 Hogs

As many as 152,000 hogs were slaughtered and processed during Madison’s peak processing years. Considering these pork houses only worked, at most, four months of the year that was quite a feat. On Dec. 31, 1855 the Madison Courier reported:

“To show to some extent the magnitude of the business in this department of the trade of the city (pork packing), we enumerate a part of shipments made during the current week. On Friday the steamers North Star, Bay City, and Chicago loaded here for Pittsburg and Wheeling, with pork, lard and bacon from the pork houses of O’Neill, Bayley & Co., E.S. Baker & Bros. and David White. The steamer N.W. Thomas, on the same day, loaded three thousand bbls. and tierces of pork, lard and hams for Boston and New York via New Orleans. The Wisconsin No. 2 starts for Wheeling today with two thousand five hundred barrels of pork, lard and hams for Baltimore. Other boats have taken away large amount of freights this week. The shipments of the last two days comprise about 6,600 bbls. and tierces pork, lard and hams, 1,000 boxes long middles and 60,000 lbs. tallow. Not a pound of this freight lay over from last week.”

The Demise

All of these pork houses fell by the wayside as time went by. There were several reasons for their demise. As towns in the interior grew, they built their own processing centers. Ever increasing railroads offered more direct and convenient transportation. Railroads also transported the pork all across the country, making it unnecessary to rely on river transportation to move the product. The reasons were many, but one old timer offers an additional reason that is perhaps overlooked. It seems Madison failed to embrace year-round slaughtering early on, perhaps resisting the cost of some means to keep the meat cool and free of spoilage. Hog producers naturally started shipping to cities that offered year-round service. No matter what reason or reasons were responsible, and no matter how she tried to make amends, Madison never regained her prominence in the pork packing field.

The Golden Age

In 1911, Charles Alling published in the Madison Courier a list of businesses located in Madison between 1847 and 1857. While this is only a partial list, is does give an idea of the magnitude and variety of commerce existing at that time.

They Make Those Out of Mud, You Know

Several brickyards were kept busy during that time of rapid development. Silas Ritchie’s yard was located at the head of what is now Jefferson Street and Jacob Luck was situated just west of St. Michael’s Church. John Kirk and John Kaufman also owned brickyards and other yards were scattered about the town. Bricklayers of that time included Ben Calloway, William Thomas, John Kaufman and Wes Hunter. A cantankerous businessman when presented with the bill for a load of bricks, which he evidently thought was excessive, once complained, “They make those things out of mud, you know”.

You’re Not From Around Here, Are You?

Jacob Shuh owned an oil and woolen mill on Crooked Creek. E.G. Whitney also owned a woolen and oil mill for a time but it was turned into a spoke factory. A third woolen and oil mill was owned by the firm of Greg and Moorehouse. This is a bit surprising because there is little evidence that sheep farming was of much importance during this time in the local area. Hogs and cattle were the cash crops of the animal world. One can only surmise that the wool for these factories was mostly imported. It’s obvious that the wool was used for the manufacture of blankets, and other woolen materials. It is likely that the oil went into soaps, lubricants and such.

So Refined

The earliest mill known in Madison was on Crooked Creek and was owned by founding father, John Paul. This mill was in operation for quite some time but by the 1840’s new and larger refineries began to flourish.

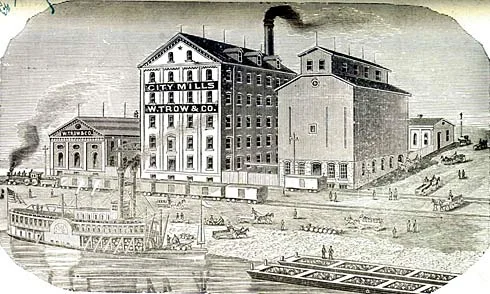

A large stone mill run by David White was located on the east end of town in the Fulton area. Interestingly, this mill produced mostly kiln dried corn meal which was shipped to Ireland during the great famine. The Magnolia Mill was a large brick building located on the northeast corner of Broadway and Ohio Streets. W.W. Page was an early miller in Madison. His large frame mill burned down and he afterwards built the Star Mills on the same site on Plum Street. At the bend of the railroad on the west side of town was the Palmetto Mills. A few years later the famous Trow Mills, built by William Trow, would be built at the foot of Broadway.

New and Used Cars

The railroad brought new business to the town. For instance, the complex at the top of the hill housed many buildings associated with the railroad. There new cars were built for the road and repairs were made to existing cars. William Clough also built cars for the railroads at his concern located in the west end of town near the river. These cars were shipped all over the country for use on many different railroads under the name of the Southwestern Car Company.

Steel Ribbons

Madison was well known for its intricate and lovely iron work. Some called it steel ribbons. There were several iron works at the time. You can still see examples of the wrought iron that came from the Madison foundries around town. Lovely fences and fancy work still are evident but much of the iron work fabricated here was shipped by steamboat down the Mississippi and was destined to ornament old homes and businesses in New Orleans. The Jefferson Iron Works was located on Second and Vine Streets, the Madison Foundry was at Elm and Ohio Streets and there was also the Indiana Foundry run by Walch and Halfenburg.

The Great Beer Controversy

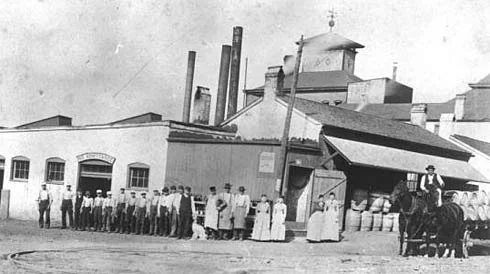

Early breweries were McQuiston’s Malt House, later called the Weber Brewery on Main Street. Greiner’s Brewery (above) was located in the Fulton area just above the river.

It was said that there was a spring on the side of the hill that produced the most wonderful tasting beer in these parts. Weber’s, not to be outdone, had a deep well in the basement that was said to impart that same wonderful quality and so there was a rivalry between the Weber Brewery and Greiner’s about town. If bar owners promised to use only one beer in their establishment they got a pretty good reduction in the price. Supposedly, if a patron had a preference for one beer over the other, he could only patronize certain bars because most did not carry both brands.

If You Need It, We’ll Make It

Lumber mills supplied industries turning out spokes, wash tubs and churns, barrels, cabinets and coffins. There was a large copper shop on the east side of Cherry Lane (now Central). The Gerratts Brass Factory made bells, boilers and any number of brass articles. They were originally based in Cincinnati but opened a shop in Madison in 1849 because there was so much work to be had. Wagons and carriages were turned out and dispatched to the rest of the country. Bacons and brooms, rope and rakes, spices and stove pipe, crackers and candles, all were in demand. If there was a need for it someone made it.

Texas Hold'em

The business atmosphere was so optimistic that it is almost impossible to keep track of the new businesses springing up and the old ones being converted. Many businesses changed hands faster and more times than a Texas Holdem tournament but like any game of chance there were risks and one’s luck does not always hold firm.

The financial situation started to change as Madison began to lose its grip on the railroad monopoly and other towns openly competed for trade. The newspapers, occasionally at first, began to report bankruptcies, closings and relocations. Then more and more notices appeared until it was commonplace.

The halcyon days were over and workers and industries moved to other towns that were just now experiencing a real growth surge. Madison never experienced such a time of prosperity and development again.

Gone Forever

On May 8, 1931, the Pennsylvania Railroad declared that short haul passenger traffic was gone from the railroads forever and that the only thing that the carriers could do was abandon train service in all instances where revenue was less than cost of operation. Therefore, the railroad said it would be forced to give up service between Madison and Columbus. Those arguments were resisted by representatives of the city of Madison. The Courier remarked, “It is safe to say that both the railroad men and those representing the city will be prepared to fight the abandonment question to a finish as neither showed any sign of retreating from their position”.

At a meeting in North Vernon a delegation representing Madison, North Vernon, Dupont, Elizabethtown and Scipio “flayed” the railroad, accusing it of poor service, high rates and lack of agents. They vowed to fight to retain passenger service between Madison and Columbus.

On May 22, before members of the Public Service Commission, the Pennsylvania Railroad defended its decision to discontinue service on four passenger trains operating between Madison and Columbus because they were a drastic loss of revenue for the company. Representatives for the city charged that worn out equipment, inadequate schedules and lack of effort to secure business had driven patrons of the community from the trains. The railroad contended that in the month of March only fifteen passengers had used the train. It also noted that baggage taken on and off the various stations totaled only four pieces during a one week period during that same month. It contended that the road expended $1,020 a month in maintaining a locomotive that pulled the passenger and freight trains on the Madison branch. Upon questioning, however, it was ascertained that the company was moving two and three cars of meat out of Madison each week with the passenger locomotive and that those receipts were not being credited to the passenger receipts. It was disclosed, also, that hundreds of carloads of coal were hauled to North Vernon to be weighed and then returned to the State Hospital, there being no scales nearer to the hospital. This led to much argument between the two sides with accusations and condemnations flying about.

An Olive Branch

Mr. Miller, superintendent of the railroad asked to make a few remarks. He said he was much impressed by the interest shown by the citizens of the community in response to the road’s petition to take off passenger train service. He stated the railroad wanted to be a good neighbor and that the community and the railroad were bound together by social and economic ties. He reiterated that the railroad could not continue to operate at the losses it was presently experiencing. He then announced that the railroad was willing to try an experiment. He proposed the use of a gas-electric car for operation between Madison and Columbus which would cost considerably less than the steam train operation. He expressed the hope that the people of the community would support the gas-electric service but, also, consider using the railroads to transport freight, as much was now being lost to movement by truck. “We will be willing to try this experiment for awhile, and see how it will work out, take off our steam train and put on a gas-electric car and see whether it will be self-supporting”. A round table discussion between members of the Madison Chamber of Commerce committee and representatives of the railroad was to take up discussion of the matter.

A Ten Cent Taxi

On June 19 the Madison Courier stated, “The schedule committee appointed at yesterday’s railroad meeting, after some discussion, accepted the schedule of trains offered by the Pennsylvania Railroad”. Also, according to the terms, all tickets would be sold at the North Madison station and all trains would terminate on the hilltop with the Victoria Taxi Company conveying passengers to and from North Madison for the sum of ten cents, including personal baggage. Provision was made for heavier baggage to be taken by truck to and from Madison. The taxi company was to be informed of the exact number of passengers so as to avoid over crowding. The terminal for the taxi was to be located at the depot on West First Street.

After some fine tuning, the final schedule for transportation on the gas-electric train was announced on June 27th. The morning train was to leave North Madison at 8:30 and arrive in Columbus at 9:55 where connection would be made with train #317 which would arrive in Indianapolis at 11:20 a. m. The evening train would leave North Madison 5:30 and terminate at Indianapolis at 10:30 p. m. The #326 train would depart from Indianapolis at 8:15 a. m., arrive in Columbus at 9:25 and connect with the gas-electric train #926 and arrive at North Madison at 11:00 p. m. Those wishing to make afternoon connections would depart from Indianapolis at 6:15 p. m. on the #324 train, arrive in Columbus at 7:09 and transfer to the gas-electric train #916 leaving at 7:45 and arrive in North Madison at 9:05 p. m.

The Doodlebug

The community was at ease with its new form of transportation for a few years. They named the gas-electric trains “The Doodlebug”. It is yet to be determined if this was a term of endearment or derision. This accommodation would prove to be only a stop-gap measure that prolonged the inevitable. Lack of interest in rail transportation and losses for the railroad brought the end of passenger service to Madison on August 16, 1935. In “Pioneer Railroad of the Northwest” Phil Anderson writes, “A coach was attached to the daily local freight to accommodate the line’s few passengers. At the same time U. S. mail and less-than-carload (LCL) shipments began to be handled by trucks. The coach was discontinued October 10, 1938, ending all passenger service on the Madison- Columbus Secondary Track”.

The Final Chapter

In the 1970’s the state legislators passed a law that states a city municipal authority could operate a short line railroad not to exceed fifty miles in length. This paved the way for the City of Madison to enter into negotiations with the railroad with the intent to purchase the railway between North Vernon and Madison.

In 1981 Madison offered the railroad $600,000 but the railroad declined, contending it was worth much more. The city filed a condemnation suit under the Right of Eminent Domain. The court ruled in favor of the city and the track was condemned between North Vernon and Madison. Under this ruling Madison would be allowed to buy the line for its appraised value. The railroad appealed the decision but in 1984 a purchase price of $307,000 was ordered by the court. Since the purchase of the railroad, repairs and improvements have been made as funds were available.

It has been a struggle to keep the road in operation. However, since Madison has no river port facilities and the closest interstate is miles distant, the city contends the railroad is necessary and the new century has seen a positive change in the road’s fortunes.

Jefferson and Jennings county businesses and industries now take advantage of the railroad finding it to be an economical and convenient mode of freight transportation. The Madison Railroad hauls a variety of commodities, including polyethylene, coal by-products and steel. It also specializes in team track operations and car storage.

There are still challenges to be met and the future is not clear but the bottom line is, the old road, after over one hundred and fifty years, is still here and still running.

Read more about today’s Madison Railroad