Home > River to Rail > Building the Railroad

River To Rail: building the railroad

Through the Hill & Dell

As Madison grew in size it also grew in economic importance. By the 19th century, Madison was one of Indiana’s largest trade centers where goods and produce were carted in from all over Indiana by rail and then shipped out all across the country by steamer. To help facilitate rail access to the north, Madisonians had to construct a rail line up the beautiful but incredibly steep hills that serve as the city’s lovely backdrop. This was only accomplished with the excavation of a slope flat and gentle enough for a pulling engine of the day to handle. The incline, as Madison’s railroad track came to be called, was famous not only for being among the steepest in the country but also for the fact that it was carved straight through the solid rock of Madison’s hills, to connect to the rail depot in North Madison. From there the Madison & Indianapolis railroad conveyed people and goods to locations all over the state.

Building the Madison & Indianapolis Railroad

Actual construction of the Madison & Indianapolis Railroad began in September 1837.

It was originally thought that the concept of wooden rails laid end to end and wedged into “gains,” a type of mortising system cut into the crossties, with an iron rail secured by spikes on top of the rails would be utilized. Instead, an improved method of all iron rails, spiked directly into the crossties, was used. In the initial stage, there being no access to a steam locomotive, horses were used to pull the cars piled with construction material.

Slowly the road advanced and a locomotive was ordered from Philadelphia. When the engine was completed, it was placed on a ship to be transported to the Gulf of Mexico where it would then transfer to the Mississippi and finally travel eastward on the Ohio to Madison.

An Inauspicious Beginning

The new locomotive was needed to celebrate the opening of the first leg of the railroad but this was not to be. During a storm at sea the heavy locomotive was pushed overboard to save the ship from sinking. This was not an auspicious beginning for the new railroad.

The directors decided their only choice was to borrow an engine from the Lexington and Ohio Railroad and the “Elkhorn” was quickly shipped by barge on the Ohio River to Madison. As the incline was still incomplete, the locomotive was ceremoniously hauled up Hanging Rock Hill by oxen to the top of the bluffs.

On November 28, 1838 the Governor of Indiana, David Wallace, and a company of prominent citizens rode to Graham’s Fork on the Muscatatuck River and back, a distance of 34 miles. At one point the train reached the phenomenal speed of 8 miles an hour.

With the celebration behind them, the directors ordered two more locomotives. They would be called the “Madison” and the “Indianapolis”. The “Madison” would make its first run on March 16, 1839 and she began regular service on April 1, 1839. The “Indianapolis” didn’t arrive on the scene unto 1841. An engine house was built on the head of the plane in North Madison in 1839. This would be the beginning of a large complex including a roundhouse, affectionately called “The Coliseum”, and forges and the foundries needed to repair and maintain the engines.

The incline was finally gouged out of the hill and was opened for business in 1841. This short portion, a mere 7,012 feet, making a climb of 413 feet with a grade of 5.89 per cent, had been the most difficult of the entire railroad.

Work gangs, comprised mostly of Irish immigrants, had labored long and hard to complete “the cut” through solid limestone and lay the tracks to the edge of the Ohio River. There was not yet an engine capable of “pulling” the hill so horses were used to pull the cars from Madison to North Madison. This continued for about seven years when a cog wheel system involving a rackrail in the center of the track was built so an engine, with attachments resembling a Rube Goldberg invention, would make the grade.

Also, during 1841, the 27.8 miles to Queensville was opened but further progress was delayed due to financial difficulties. In 1847 the line was completed to Indianapolis. There was great fanfare for the event. It was the beginning of great expansion for the interior, an era unequaled at any point in Indiana’s history.

By January of 1848 there was regular rail traffic between Madison and Indianapolis. The north bound passenger train left Madison at 8 a.m. and arrived at the capitol at 2 p.m. The southbound left Indianapolis at 7:30 a.m. and arrived in Madison at 2:30 p.m. Freight left Madison and Indianapolis at 5 a.m. There was no regular passenger service on Sunday but there were occasionally Sunday excursion trains for special events.

Constructing the Incline

While the hills embracing the town of Madison were lovely to behold, they proved to be a stumbling block to the progress of the Madison and Indianapolis Railroad.

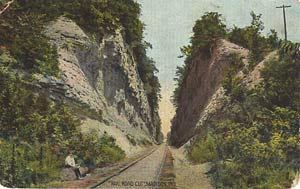

There was no direct way to get the railroad out of Madison except by means of an inclined plane. It would be necessary to make a climb of 413 feet and achieve a grade (slope) with a rise of 113 feet per mile. This was the equivalent of an average grade of 5.89 per cent and it would attain a length of 7,012 feet. This gave the Madison incline the dubious honor of being the steepest line-haul grade in the country. The terrain was of solid rock and the only means of carving the incline was by hand labor and blasting with black powder charges to loosen the rock. The mostly Irish workers would then laboriously haul the stones out of the right-of-way with mules and horses. Some of the rock was selected for use in the building of St. Michaels Catholic Church.

Five Years of Work

The incline, or “cut”, was actually built in three stages by three different contractors. The upper third was contracted to John Giddings, the middle to Joseph Hendricks and the lower cut was done by the Flint and Stough firm. Overall construction was supervised by Col. Thomas A. Morris, chief engineer. The lower cut plunged about 100 feet deep and the upper cut only about 40 feet. The Hendricks crew had the honor of achieving the deepest cut. Their portion attained a depth of over 125 feet. The right-of-way for the track was 25 feet wide and the distance between the rails was the standard gauge of 4 feet, 8 1/2 inches. The rails used were made of iron and known as “T” rails made in England. Ironically, there was no steam engine available so the heavy cars laden with materials were pulled by horse. Slowly, the road advance up the hill and there it connected with the line from the north. The incline had been started in 1836 and was finished in 1845. It had taken five years of arduous work and one wonders that it was accomplished at all.

First Trip Up the Incline

Article: Madison Courier from November 6, 1841

The citizens of Madison were gratified on Wednesday morning last, with a spectacle unlooked for by the people generally as well as ourselves. It was the action of the common Locomotive and its train upon the plain of the Railroad between the depot on the hill and the river. The track being laid and in a condition to receive the cars, about 8 o’clock in the morning the locomotive came down the plain and proceeded up the river to the principal wharfs of the city. There it paused until every position where a man could stand, on the engine itself, on the tender, and on a burthen car attached to them, was entirely occupied. It then moved with great velocity to the plain, which it ascended with ease, and arrived at the depot in little more than eleven minutes, from the vicinity of the wharf from which it started, a distance of about two miles, and carrying between 80 and 100 passengers.

Among those who passed up the plain on the cars, we mention the Rev. Allen Wiley and the Rev. John Smith, of the Methodist Episcopal church, and Gov. Noble (right), the Fund Commissioner of the State, who considered, as we understand, the question settled, that steam power will be all sufficient on the plain, and that passengers and freight from the interior need not be much longer taxed and delayed by leaving the cars at the depot and employing hacks and wagons to the hotels and business houses of the city. We are among those who have been incredulous as to the propriety of the location and heavy expenditure of the plain, but these having taken place, we congratulate our fellow citizens of the back country in the increased comfort and facilities they will have in visiting and doing business in our place; and when we take into view the vast trade in Wheat and Salt between this point and the central counties of the State, we feel certain that an increased interest will be felt everywhere in this matter. The wheat from the back country, we are told, has been the present year, at least three to one greater than any previous year.

To the present Fund and Internal Improvement commissioners of the State we are mainly indebted for the progress of the work during the present year. They, with the aid of several enterprising citizens of this place, have given impulse to the work by applying a portion of the last appropriation to it, and the whole line, with a very few exceptions, (unfinished short sections) is graded and bridged from this point to Edinburgh. The track is laid and cars running as far as Griffith’s about 29 miles from this place and could iron be procured the residue of the appropriation not yet expended, would probably lay the track to Edinburg, about 29 miles further. This cannot fail to awaken additional interest in the next Legislature to the work; for, finished that far, private enterprise would accomplish, and that speedily, the remaining 28 to 30 miles to Indianapolis, and the road would at once yield a revenue to the State, and be of incalculable value to the whole interior.

The Rueben Wells Locomotive

Most every railroad had a locomotive that became part of railroad folklore. The B & O had its Tom Thumb and there was the Casey Jones and the Wabash Cannonball, to name a few. On the Madison line, the hero of the iron rails was the Reuben Wells. After the consolidation of the Madison & Jeffersonville lines, Reuben Wells, the master mechanic of the Jeffersonville shop, determined that the problem of the steep incline at Madison had to be solved. Wells believed that a properly located center of gravity and enough weight to assure adhesion to the track would enable his engine to climb the grade. He set about to design and over see the construction of his namesake, “The Reuben Wells”.

Reuben Wells, himself, made the following report to the board of directors of the JM & I railroad:

“A new tank locomotive named the Reuben Wells, for working the inclined plane at Madison without the use of the cast-iron rack and pinion as heretofore used, was built and completed in the shops of the Jeffersonville, Madison & Indianapolis Railroad at Jeffersonville in July, 1868, since which time the engine has been in constant service, doing the work there in a satisfactory manner.”

Here’s how The Madison Daily Courier proclaimed the day on July 18, 1868:

THE NEW LOCOMOTIVE.—-The new locomotive engine Reuben Wells, built at the company’s shops in Jeffersonville, for use on the inclined plane, arrived on Thursday and was put in service yesterday morning. She is large and powerful, weighing seventy tons or 140,000 pounds. Yesterday morning she pulled the passenger, mail, baggage and express cars up the hill in the remarkably short time of nine minutes. (The time usually occupied by the old mode of cogs was from twenty-five to thirty minutes). On Thursday, a train of nineteen freight cars was brought from North Madison to this city without the use of a break. She is a perfect success as regards power and speed for the purposes for which she was built, but too heavy for the track, which, in our judgment will necessitate the building of a new track. She is named after the builder, Reuben Wells, master mechanic of the shops in Jeffersonville. Josh. McCauley, for many years engineer of the “Brough” has charge of her now.

It was an impressive machine. Here are the statistics of the engine as described by Reuben Wells:

Cylinders: 20 inch diameter and 24 inch stroke

Driving Wheels: 5 pair with 44 inch diameter

Boiler: 56 inch diameter, 7/16 outer shell

Boiler Tubes: 201 two inch tubes, each 12 feet long

Firebox: 5-feet 3-inches long by 5-feet 3-inches deep by

4-feet wide on the top and 3-feet wide on the bottom

Heating Surface: 116 square feet in box; 1,262 square feet in boiler

Water Capacity: 1,800 gal. in 2 tanks on either side of locomotive

Weight of Locomotive: 56 tons in working order

Wells continued: “With the experience had in working this engine on the plane under all conditions of the rail, and in all kinds of weather through the fall and winter, I am satisfied that the plane can be worked as safely with engines obtaining their adhesion from the rails only as by the method heretofore used. The time required to ascend the plane with a full load is one-half less, and with passenger trains about one-third less, than that required by engines using the rack and pinion, while the cost for repairs will be greatly reduced. The entire cost of the engine when completed, including cost of patterns, was $18,345.30.”

Brough's Folley

When the state relinquished control of the railroad to a private corporation, a provision in the contract required the new company to build an alternate route between Madison and North Madison, eliminating the use of the troublesome incline.

John Brough, the capable president of the M & I Railroad devised a plan to comply with the provision. He proposed a lower grade line, a little over four and one half miles long be constructed east out of Madison, along the edge of the hills. The line would veer off into the Clifty Creek Valley, within what is now Clifty Falls State Park, and would traverse the rough area using trestles and tunnels when needed to emerge on the upland. From that point the road would continue to the next existing line a little north of Madison.

In an annual report in 1852 Brough stated:

“The route for the new southern terminus, to avoid the inclined plane at Madison, has been located during the year, and, at present, about 700 hands are employed in its construction. It leaves the present line at the foot of the plane, crosses Crooked Creek, and passes west, along the side of the hill, to Clifty Creek, thence up Clifty to the Chain Mill fork, and up that to an intersection with the main line, near the four mile post from Madison. The grade will be heavier than I desired, being about 100 feet to the mile, on straight line, and 9 feet on curves. The work is very heavy, and, being in so small a space, will require more time to perform it. There will be two short tunnels, in rock, that can be more rapidly constructed, and at less expense, than through cuts. The length of the new line is 4 ¾ miles, making an addition of ¾ mile to the length of the road. With an assisting engine it can readily be worked by ordinary motive power. The prospects of the road during the present year are bright and cheering. This year will launch us into the midst of the competition that has been for a few years, gathering around us. The road will, in a short time, be well prepared to meet it.” This optimism was short lived as a year later Brough reported: “This work….like most other where uncertain materials are to be encountered, will considerably exceed its cost the estimates made upon it….It is estimated that about $115,000 will be necessary yet to finish the work.”

In 1853 Brough believed it would take only three more months to finish the job, but work was stopped when money to fund the project ran out. The plan was probably a good one and would probably have solved the problem of the incline but because of his involvement in the project and its ultimate failure, it became known as “Brough’s Folly”.

Today, you can still find vestiges of Brough’s folly at Clifty Falls State Park including stone trestles (at right) and a railroad tunnels. Naturalists at the state park regularly offer tours of the remains.